2. Do You Speak Georgian?

Do You Speak Georgian? is a narrative podcast and serial memoir set in the Republic of Georgia. Join your host, Alicia Michelle, on a whirlwind adventure in the South Caucasus, where you’ll hear about the dark side of international travel – the side mainstream travel bloggers don’t share on Instagram.

Do You Speak Georgian? reflects the author’s recollection of events. Some names, locations, and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of those depicted. Dialogue has been recreated from memory.

Maps were one of my first special interests.

Once something became a special interest, I had to know everything about it. Anything – from cats, to house music, to makeup – had the potential to become one.

A laminated map of the United States served as my placemat at the family kitchen table. A map of Virginia hung on my bedroom wall. City names. Borders. Elevations. All were fascinating. I’d spend hours rotating a globe in my room, feeding my imagination on cotton candy nations. In a single afternoon, I became the youngest person to circumnavigate the world.

I wondered. What kind of people lived in places like Tokyo and Timbuktu? I worried. Were Hungarians hungry in Hungary? I wailed. Did eating turkey meat mean I was eating Turkish people?

The world had two Georgias. Odd. One was in America. The other revealed itself whenever I turned the globe 180 degrees. What was this other Georgia? Why were there two of them? One of them had to be an imposter for sure.

I wouldn’t find out more about the other Georgia until high school.

When I was eighteen, I popped into a local bookstore to escape central Virginia’s bitter January winds. I scoured the history section, a new special interest I developed while taking a twelfth grade world history course. The teacher, a chain-smoking divorcee with a love of profanity, deviated from dry standardized curriculum in the name of challenging his students. He said history was more than just timelines and powdered wigs. It was a story. It was alive. And every one of us was part of it.

Like many budding armchair historians, the rise and fall of fascism was my gateway drug.

Berryman, Clifford Kennedy, Artist. Wonder How Long the Honeymoon Will Last?. , 1939. Oct. 9. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016679213/.

Once introduced to history, I proceeded to make myself at home in her darkest chapters. Into the shadows of those who accomplished terrible things, of Marxist revolutionaries, of dictators, of those who came from nothing and proceeded to pave the road to hell with their good intentions. Something about humanity’s abyss spoke to me. To something deep within my subconscious. I couldn’t stop starring into it. It couldn’t stop starring into me.

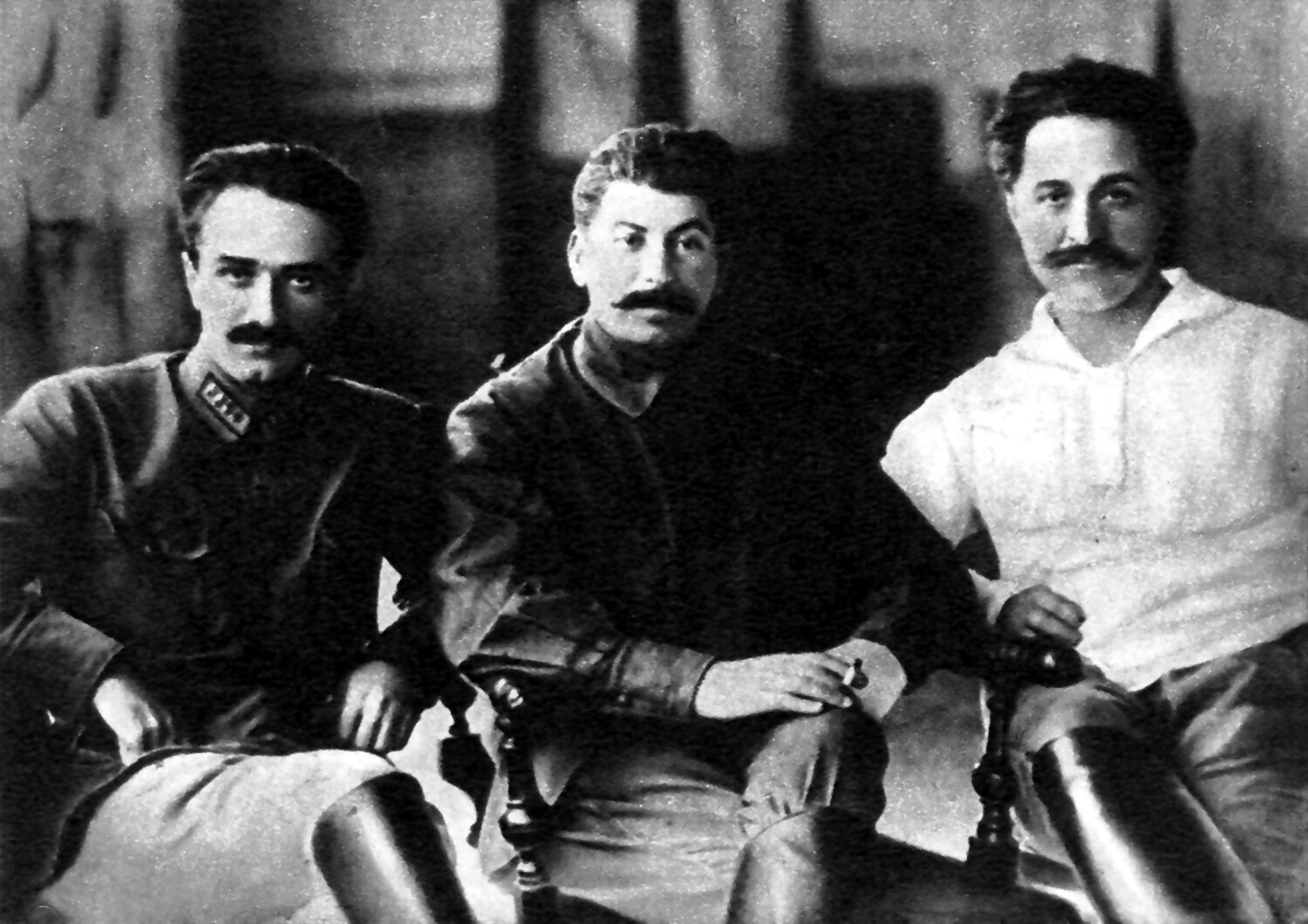

I scored my next hit once I found an eye-catching book, one that stuck out amongst the paperweights on Civil War history, a genre that was understandably popular given my hometown’s location. At roughly 300 pages long, its aesthetically pleasing white cover featured an old mugshot of a prototypical hipster. A young man with a scruffy beard and effortlessly draped scarf. Above his head of luxuriant black hair, bold crimson text read: Young Stalin.

I flipped to the book’s first page. There she was again. Georgia. On a historical map of the Russian Empire.

I bought the book immediately.

19th century South Caucasus. Potto, Vasily (1899). Исторический очерк кавказских войн от их начала до присоединения Грузии [Historical studies in the Caucasian Wars from the beginning down to the annexation of Georgia]. Tiflis: Caucasus Viceregal Chancellery Press.

Like the title suggested, Young Stalin was a biographical account of the eponymous Joseph Stalin’s early years. Before becoming the mass murderer we all know and love, Stalin was born with a name possibly more terrifying that the Great Terror he came to implement. Iosif Vissarionovich Djugashvilli. Contrary to my original belief, Stalin was Georgian. And like many men who grew to become 20th century Big Bads, Stalin had small town origins. He spent his childhood in a village called Gori, located in central Georgia.

Like my history teacher, the book’s author, Simon Seabag Montefiore, took research from primary sources and transformed it into a story. A story begging for film adaptation, featuring narrow escapes from brutal Siberian prisons, money laundering in filthy Azerbaijani oil fields, and juicy Bolshevik gossip in stuffy Viennese salons. I, an average suburban adolescent, found myself seething with bizarre jealousy as I gobbled up page after page of Young Stalin. How cool it must have been, to be at history’s helm.

Larger than life historical figures came packaged with a larger than life setting. Georgia, I learned, was home to mountains that put The Lord of the Rings to shame. She had wine. She had table-buckling feasts. She had choir boys that carried bullets in their vest pockets and daggers on their belts.

Georgia sparked a fire within me. I had to – I needed to go there.

I spent the next six years searching for a reason.

Tolkien, eat your heart out. Nelson, Amy (2011). Mighty Towers. Flickr.

“But…why Georgia?” my friend Helen asked between increasingly large sips of her frozen margarita at a local chain restaurant. She earned 30k per year at her nonprofit job. Her rent kept rising. Her salary didn’t.

Including Helen and me, there were five of us in my ragtag crew. Chase, a self-described bro with a heart of gold. Alex, who wagered the economy would improve by the time he finished a PhD. And Safiya, who considered overstaying her student visa as an alternative to returning home to Saudi Arabia.

Brought together in graduate school, we commiserated over the misery that was trying to find gainful employment in a city where possessing a master’s degree was equivalent to holding a high school diploma. What we would do with our lives was a frequent topic, a question that continued to go unanswered as the summer of 2014 passed us by.

I gave my two weeks’ notice at National Bikes after reviewing the congratulatory email on my 30-minute lunch break. And I had forwarded the signed teaching contract to the Georgian program officer as soon as I got back to my apartment.

In a generation where it was a rite of passage to study abroad, backpack, or au pair in sexy places like France or Italy, I continued to be enraptured by Georgia. Partly because the opportunity to travel to sexy places never presented itself. And partly because Georgia had become another special interest.

Yes, France and Italy had their appeals – bread, booze, and boys – but my attention was always diverted back to Georgia. While Western Europe offered a gamut of cultures just foreign enough to enchant, her low barrier of entry meant she was just familiar enough to keep American visitors comfortable. Georgia was the opposite. Challenging, just beyond the event horizon of comfort and familiarity. At the end of the day, Georgia offered many things Western Europe didn’t.

Adventure. A lenient immigration policy. And most importantly, time.

Time to figure out what I wanted to do with my life.

Time to escape what awaited me had I not signed the teaching contract; indefinite months of firing electronic job applications into an abyss of an entirely different kind.

“What language do people speak in Georgia?” Chase wondered before flagging down a waiter and ordering another Long Island iced tea.

“Georgian.” I replied.

“Do you speak Georgian?”

I shrugged. “Not a word.”

“What will you do there?” Alex added.

“Teach English.” A piece of mint from my mojito had lodged into my straw.

Prior to 1991, the last time Georgia was a sovereign nation was April 1918.

Portions of Georgian history are enmeshed with Russian history. The Russian Revolution is Russian history’s most user-friendly access point, and coincidentally, good background for understanding development in modern Georgia.

To summarize the lead-up to 1917, Tsar Nicholas II had one job.

To bring the Russian Empire out from the preindustrial funk that festered in every corner of society.

He entered World War I instead.

And so began a series of events that snowballed into the Russian Revolution. Being Russian history, things got worse, with revolution leading to the Russian Civil War. Following Nicholas II’s forced abdication of the throne, a veritable smorgasbord of political forces, with Bolsheviks (“Reds”) and Romanov loyalists (“Whites”) being the main players, scrambled to fill the power vacuum. And as the Russian Civil War carried on between 1918 and 1921, the territories that once made up the Russian Empire were left to fill power vacuums of their own.

In true Marxist revolutionary fashion, the South Caucasus – Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia – organized into a mouthful of an alliance. The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. Also in true Marxist revolutionary fashion, disagreements over governing philosophy meant the alliance quickly dissolved.

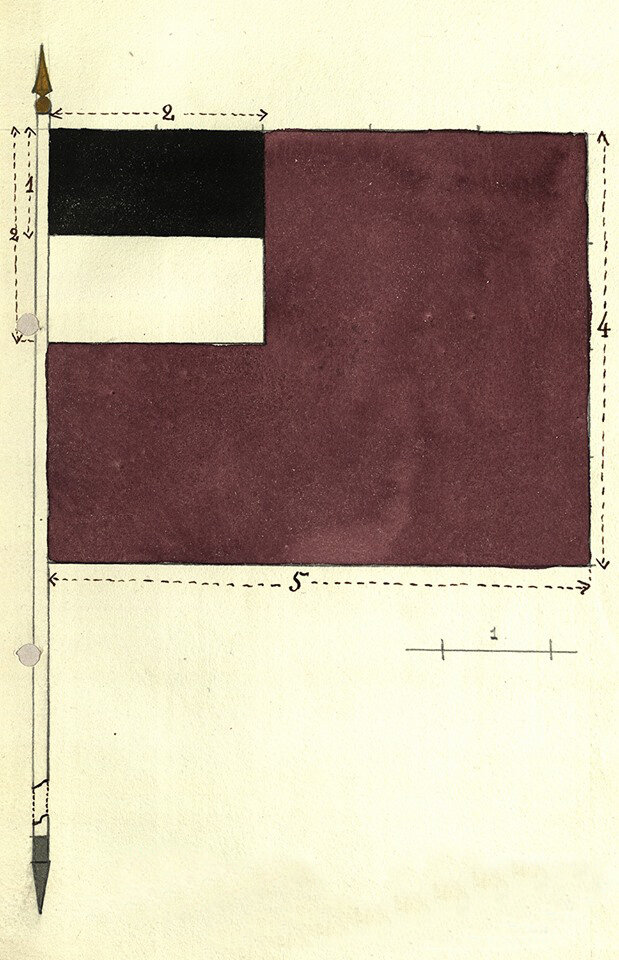

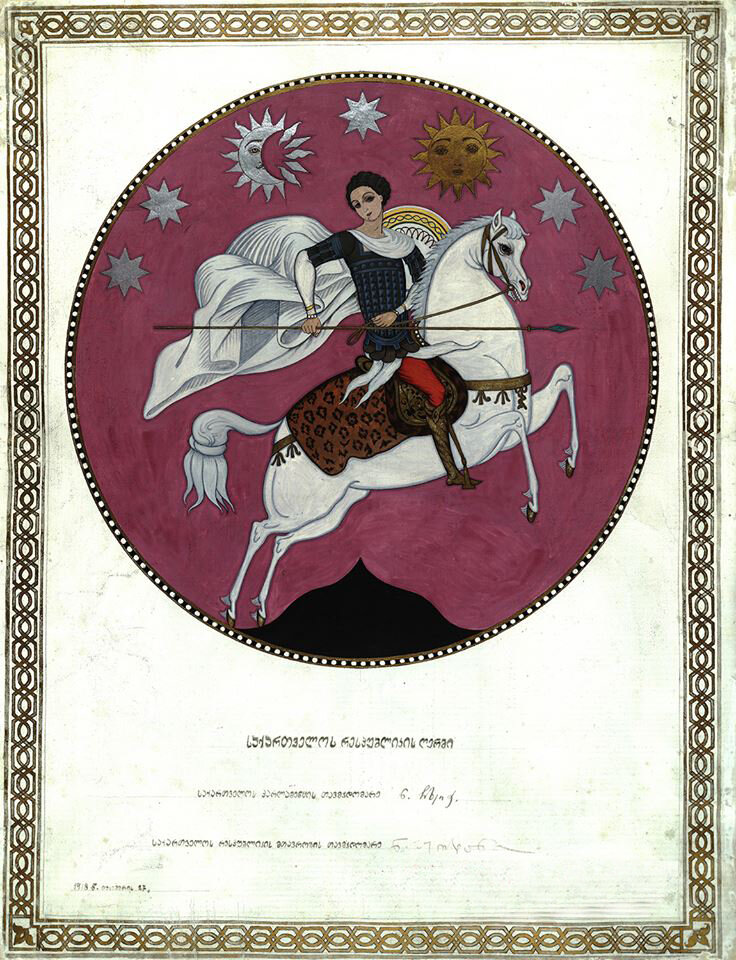

From the ashes rose the Democratic Republic of Georgia.

Independent Georgia, however, was a flash in the pan.

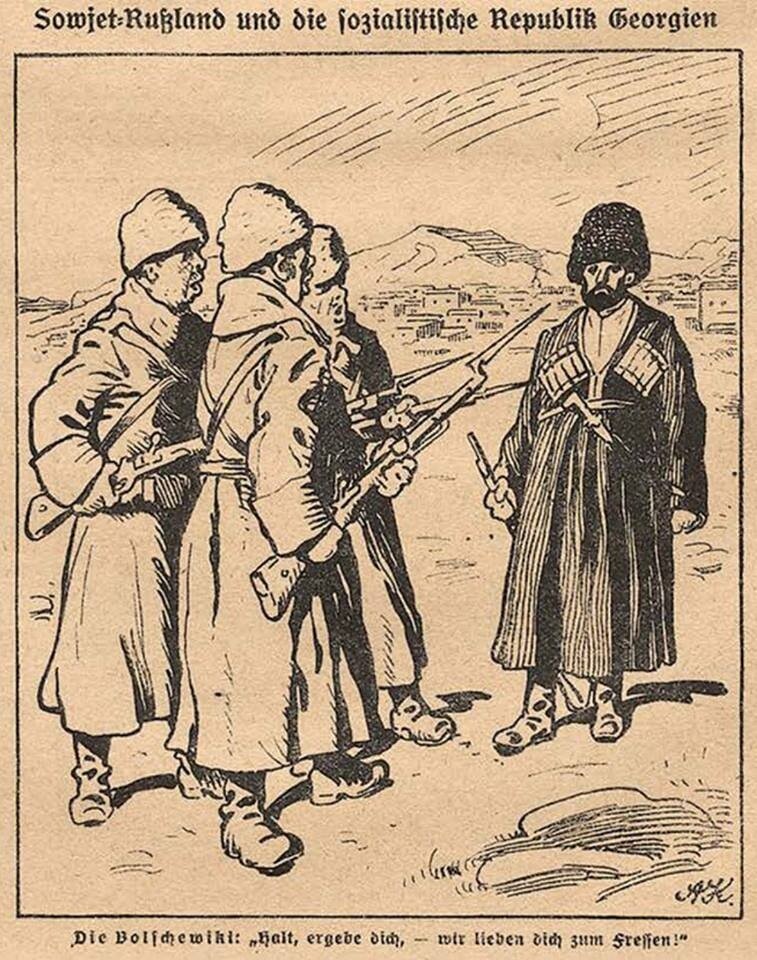

Stalin was Georgian, but he was only loyal to one thing. The revolution. Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks knew Mother Russia couldn’t call herself a mother if she had no children; the Red Army, with Joseph Stalin as one of its organizers, encroached upon the South Caucasus in 1920. Tbilisi, already cracking beneath political pressure from the Kremlin, didn’t stand a chance. In February 1921, Georgia and her Caucasian ilk were pulled back into Russia’s orbit, this time under a new family name.

The Soviet Union.

Though the Soviet Union organized under a policy called “national dellimination”, where borders of individual Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs) were drawn according to ethnicity, all things Soviet Russian – language, culture, and policies of spiritual extermination – were used as a way to consolidate Bolshevik power and legitimize the Marxist regime. One aspect of this political strategy, called Russification, meant all citizens of the Soviet Union were required to learn Russian as a second language. Specters of Russification could still be seen in 21st century Georgia, where every Georgian roughly above age 30 could read, write, and speak fluent Russian.

A Georgia that spoke Russian was a Georgia still haunted by a painful past; following the tumultuous 90s, the Rose Revolution in 2003 put Georgia on the path towards democracy. With the first steps toward democracy came Georgia’s desire to reorient towards the European Union.

Teach and Learn with Georgia (TLG) was founded in 2010, launched by former President Mikhail Saakashvili and funded by the Georgian Ministry of Education and Science. TLG’s primary mission was to replace Russian with English as Georgia’s second language. Similar to the US Peace Corps, TLG recruited qualified applicants from English speaking countries and assigned them to various villages across Georgia, where they’d co-teach English lessons and implement community projects. Previous teaching experience was not required.

TLG’s secondary mission was to facilitate globalization. In a rapidly globalizing world, the ability to speak English opened doors. It meant a generation with access to more education. It meant exposure to new ideas, to ways of thinking that could potentially propel Georgia from beyond the shadows of the Iron Curtain.

Teaching English was a legitimate, albeit risky, option for casualties of the Great Recession. Need a job and need it now? China is always hiring. Need a salary because no one will pay you what you’re worth? South Korea’s got your back. Want to escape Sally Mae by disappearing off the face of the earth? Vietnam is calling your name.

Beneath sleek photos of Tbilisi’s restored historic quarter and wide-eyed Georgian children, TLG gave me the reason I had been looking for. Gainful employment; assisting Georgian English teachers with lesson planning and implementation. A livable salary; 600 Georgian Lari (GEL) per month after taxes (equivalent to roughly USD 300), three times the average Georgian teaching salary. Affordable housing; a home where my rent payment was a cool 200 Lari (roughly USD 100) per month.

It was a package deal. A win-win. Volunteers got to be part of something bigger than themselves. They’d help Georgia self-actualize and touch the lives of a younger generation. In return, volunteers would be granted the adventure of a lifetime.

Statue of Mother Georgia, aka Kartlis Deda.

“How long will you be there?” Safiya inquired.

“One year.”

Prior to being accepted to TLG, the longest I had been abroad was two weeks.

I’d be away for a full academic year. Four seasons. 12 months. 365 days.

“Where will you live?”

“I don’t know.”

Volunteers were typically placed in a host village with a host family. All host families were required to provide volunteers with a private bedroom and two meals per day. The homes were assessed for suitability by TLG officials prior to assigning a volunteer. As for where this placement was, I wouldn’t find out until after I arrived in Georgia.

“When will you leave?” Safiya wondered.

“I…don’t know.” She couldn’t see how my thigh bounced up and down beneath the table.

When it came to travel, I liked to plan. Planning was how I felt safe. Safe was how I felt, in pre-booked hotel rooms and activities planned by the hour, in previous flings with the UK and Germany. I was a walking contradiction. I craved adventure, but sought security in paying for window seats and memorizing street names.

A contract with TLG guaranteed all-expense paid flights to and from Georgia. The flight, to be booked through one of the few airlines with service to the South Caucasus, would depart in three weeks. When would I receive the tickets? What airline would I fly with? Would I be able to sit by the window? That was now up to the Georgians to decide.

Anxiety bubbled in my gut. I craved adventure, but adventure was a broad term.

What had I gotten myself into, my intuition asked.

I drowned it with liquor.

![19th century South Caucasus. Potto, Vasily (1899). Исторический очерк кавказских войн от их начала до присоединения Грузии [Historical studies in the Caucasian Wars from the beginning down to the annexation of Georgia]. Tiflis: Caucasus Viceregal Ch…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e0d1583e872050321c8e939/1578002977291-TXBW1C2CMR4Y7VB3HYET/1443px-Caucasus_map_1799.png)